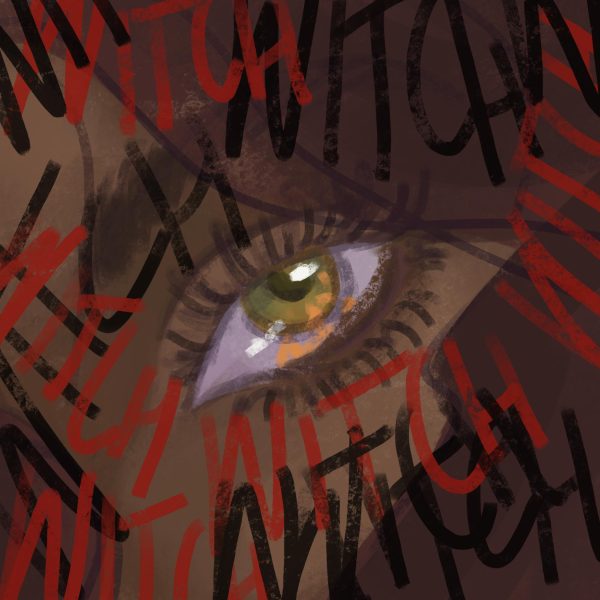

While you prepare for the coziest months of the year by drinking pumpkin spice lattes and watching Hocus Pocus, you can’t help but wonder about the true origin of witches. How did we come to think of witches as women who steal children from their houses and curse little boys to be cats for centuries? Do they wear all black and ride their brooms across the moon whilst cackling? Whether it be misogyny or just a little hocus pocus, the imagery and ideas of witchcraft are embedded into our history.

The European settlers of Massachusetts brought with them a unique mindset and belief structure that reflected their religious convictions and an unwavering understanding that if anything went badly, it was because they deserve God’s wrath. The first wave of European migration coincided with a surge of witch hunts across Europe, so the settlers were already on the lookout for signs of witchcraft. On one of the ships, an English settler by the name of Mary Lee set out for Maryland. Once on the ship, she was the target of witch rumors, and when the ship ran into unsafe weather conditions, she was persecuted and hung on board to ensure the safety of the other passengers. No matter what colony they landed in, the settlers brought their prejudices with them.

It’s 1692. In the midst of the colonies, the enchanting village of Salem had its own problems: disease, death, land issues, and the rumor of witches. After girls from the settlement were accused of dancing scandalously in the woods, rage sparked within the community. The girls slowly began to have fits and were ridden with illness. It was said to be witchcraft, and the girls quickly blamed the older women of the settlement. They named three witches as the tormentors: Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba. These women all had something in common—and it wasn’t being witches. The targets were all elderly, poor, unmarried, outspoken, and deemed a nuisance by the community.

At the time of the trials, Sarah Good denied any presence of witchcraft, but when she failed to recite a prayer, she was proven guilty and hanged. Osborne tried a different tactic, attempting to blame it on a dream she had of a Native American man leading her away. Despite her persistent claims, no one believed her story. Every time Good or Osborne spoke, the accusing girls shrieked and writhed about, which led everyone to declare the witches guilty once again, as no voice of a mortal could cause such anguish.

Tituba, rather than denying the allegations, immediately offered her full confession. By confessing to the charges, she received mercy. For days, Tituba entertained the court with stories of her becoming such an evil. She confessed that Osborne and Good had told her to attack the townspeople. More ominously, she spoke of a tall man in black who forced her to hurt the children, tempting her with jewels and money if she served him for six years. Tituba testified that the man brought with him a book, with her name signed into it. Upon questioning, she revealed that other names of people in the town were in there too, unfolding more mystery and drama.

After Sarah Good’s execution, the hysteria in Salem continued to grow. Sarah Osborne died in jail, and Tituba remained imprisoned, eventually being released and disappearing from historical records. Many others followed, with over 200 people accused and 20 executed. The trials left a lasting impact on the community, serving as a grim reminder of the dangers of mass hysteria and the consequences of scapegoating. The Salem witch trials remain a dark chapter in American history, illustrating the perils of fear and superstition. So as the moon rises and the shadows deepen, remember the tales of Salem’s witches

Violet Binczewski • Oct 10, 2024 at 10:22 am

This article is so well written and thoroughly researched. Not only was I interested in what you were saying, but I could not stop reading, GREAT WRITING! Caroline you did such a great job and I can’t wait to see what other amazing things you write for the Campanile!